Understanding Subcutaneous Emphysema: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments

If you suddenly develop swelling under your skin that crackles when pressed, you may have a condition called subcutaneous emphysema. While alarming, subcutaneous emphysema itself is typically not dangerous. However, it’s often a sign of injury or underlying lung disease. Getting prompt treatment can prevent complications.

What is Subcutaneous Emphysema?

Subcutaneous emphysema refers to the abnormal entry of air under the skin. It causes swelling as pockets of air accumulate in the fatty tissues and muscles beneath the skin surface. The swelling has a distinct crackling, crunchy feel when pressed due to the trapped air bubbles.

Subcutaneous emphysema most often occurs on the neck, chest, and face since these areas are closest to potential air leaks in the chest cavity. However, if severe, air can track along fascial planes (connective tissue) and spread widely throughout the arms, torso, and down to the feet.

Causes of Subcutaneous Emphysema

There are a few ways air can escape from the lungs into the subcutaneous tissues:

- Lung trauma – Any injury that damages lung tissue can cause air leaks. Examples include gunshot or stab wounds to the chest, broken ribs that puncture the lung, and medical procedures like lung biopsy.

- Airway ruptures – Vomiting very forcefully can rupture the throat and trachea (windpipe). Air from coughing exits through the tear into the neck tissues.

- Complications of mechanical ventilation – Patients on ventilators are at risk because high airway pressures used to inflate damaged lungs may cause alveolar ruptures. Also, the ventilation tubing itself could perforate and leak.

- Lung disease destroying alveolar walls – Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, pneumonia, and lung abscesses slowly destroy the tiny air sacs in lungs. Eventually, the walls rupture, releasing air around the lungs.

The above situations allow air to escape from the lungs/airways into the pleural space between the lungs and chest cavity, causing a pneumothorax lung collapse. The free air then dissects its way along fascial planes into the subcutaneous tissues.

Symptoms of Surgical Emphysema

The hallmark sign of subcutaneous emphysema is pronounced swelling of the skin that crackles and crunches on palpation. The amount of swelling depends on the size of the air leak and location. Small leaks may only cause minimal subcutaneous air. But large leaks can be life-threatening as air tracks extensively through the chest, neck, face, and down the arms/torso, greatly compressing surrounding structures.

Other symptoms that may accompany subcutaneous emphysema include:

- Chest pain

- Difficulty breathing

- Wheezing

- Tightness in the throat (stridor)

Complications

While subcutaneous emphysema itself causes only mild symptoms, untreated severe cases lead to tense swelling that compress vital structures. Possible complications include:

- Airway compression – The trachea and bronchi can collapse as swelling narrows their diameter. This impedes airflow to the lungs.

- Breathing impairment – The chest wall stiffens, preventing proper expansion/contraction of lungs.

- Impaired blood flow – Swelling presses on and constricts blood vessels.

- Infection – Bacteria gain entry through the tissue tear into sterile areas like the mediastinum.

- Pneumothorax – Ruptured lungCreating an escape route for air to exit causes lung collapse.

- Respiratory failure and death – Air hunger eventually results without adequate gas exchange in lungs.

Diagnosing Subcutaneous Emphysema

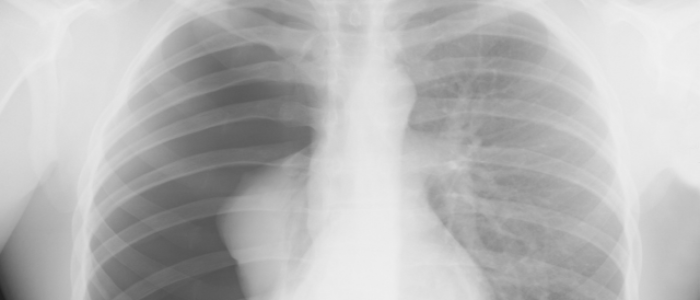

Doctors first assess a patient’s medical history for trauma, injury, vomiting, lung disease or procedures that could cause air leakage. Signs of respiratory distress like low oxygen also provide clues. They then conduct a physical exam, which reveals the characteristic subcutaneous crackling.

The following tests help pinpoint the origin of air leaks:

- Chest X-ray – Shows air bubbles lining chest wall tissues plus any lung collapse.

- CT scan – Provides detailed 3D view of air pockets to reveal size, location, and origin.

- Bronchoscopy – Camera probe down airways detects tears.

Treatment for Subcutaneous Emphysema

Treating subcutaneous emphysema involves:

- Stopping additional air entry

- Draining air already dissected into tissues

- Allowing leaks to heal

Stopping Air Entry

Preventing further leakage prevents worsening of swelling compression complications. This requires targeting the precipitating cause:

- Lung trauma – Surgical repair seals damaged lung tissue

- Esophageal/tracheal ruptures – Restrict oral intake to rest the structures. Tears typically heal in 7-14 days without intervention.

- Mechanical ventilation – Evaluate pressures and tubing placement

- Lung disease – Treat the underlying COPD, pneumonia etc. Adjust ventilator settings.

Draining Existing Air

Several drainage techniques remove subcutaneous air, including:

- Small skin incisions – Cutting through skin releases air closest to surface via pressure gradient

- Large bore angiocatheters – Inserting a wide hollow needle deep into tissues provides low pressure exit route

- Subcutaneous catheter – Tunneled catheter with side holes threads through the fascia for continuous passive drainage.

Promoting Tissue Healing

Most tears heal spontaneously within 2 weeks if lung trauma is addressed and further air leakage prevented. Some tips to help the process include:

- Respiratory therapy – Teaches techniques like pursed lip breathing to avoid additional alveolar rupture

- Activity restriction – Limits exertion to allow natural healing

- Follow-up exams – Monitors resolution of air pockets

Prognosis for Subcutaneous Emphysema

Most cases of minor subcutaneous emphysema resolve on their own without consequences. However, the prognosis depends greatly on the extent of swelling and how quickly air compression gets relieved before it impacts breathing and blood flow. Giant subcutaneous emphysema with diffuse swelling requires urgent treatment.

With proper supportive management though, the overall prognosis is good. Most patients recover full function once the precipitating lung injury or disease gets treated.

Conclusion:

Subcutaneous emphysema can seem alarming when suddenly faced with odd crackling and swelling under your skin. However, while uncomfortable, the trapped air itself causes little harm beyond cosmetic issues from puffy tissues. The real danger lies in the precipitating lung injuries and diseases allowing air escape in the first place. These require prompt treatment to heal tissue, stop additional leakage, and drain air pockets before compression sets in. So if unexplained skin crackling develops, especially accompanying chest trauma/pain or respiratory distress, seek rapid medical evaluation. With proper support care, most cases, regardless of severity, resolve back to normal lung function. Keeping the big picture view allows bypassing the sensations of subcutaneous air itself to address the root causes.